Serious Gaming for Home Improvement

Sadhana Jagannath - Imperial College London

At last year’s Annual HSA conference (2024), I had the pleasure of co-presenting the use of ‘Serious Game’ methodology to better understand home improvements and modifications for healthy ageing in place. This creative methodology allowed unravelling the complexities that older adults, their families, professionals face when making decisions about home improvements needed to allow independent and happy ageing in people’s current/preferred homes.

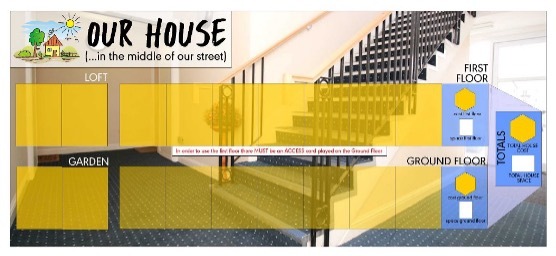

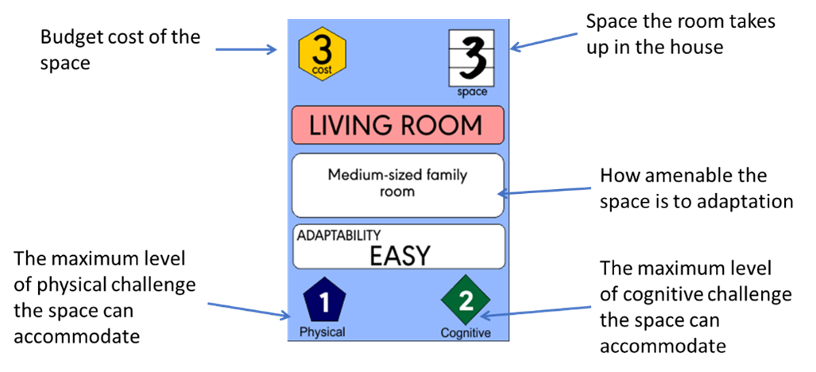

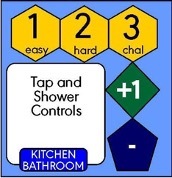

‘Our Home’ game board (top) and space cards (bottom) designed in partnership with Stone Paper scissors.

Homes are usually not designed to support a decline in physical and cognitive faculties as we age, needing many adaptations and modifications to make them more accessible and suitable for everyday living activities such as bathing, cooking, sleeping, moving in an out of the rooms and the house, and provide an enjoyable ageing experience to people. Due to design limitations, funding restrictions, and a lack of knowledge around supporting cognitive ageing at home, the process of availing modifications to home are often complex. Further involvement of various actors and mechanisms add to the complexity of navigating this process. The serious game played an important role in allowing older adults, their families, health, care and housing professionals and policy makers to explore their thought processes and challenge their rationale for decisions made.

The game was developed as an innovative methodology for the UKRI funded Designing Homes for Healthy Cognitive Ageing (DesHCA) project based at the University of Stirling, in partnership with Jim Wallman, Stone Paper scissors. The project aimed to understand what good housing design looked like for not just physical but our cognitive ageing at home - such as living with dementia. And identify impactful and scalable design features working with a range of stakeholders and partners covering architects, housing providers and managers at housing associations, charities, and council, occupational therapists and carers, policy makers and mostly importantly the older adults themselves.

I co-presented this work at the HSA 2024 conference with Prof Vikki McCall (University of Stirling) who led the development and use of serious game for the DesHCA project; who with Dr Jenny Preece (University of Sheffield) applied the tool to build an evidence base of home improvement services and processes in England as part of a national evaluation with the Centre for Ageing Better. At this talk, I presented insights from a playtest that I hosted with a group of older adults in England.

The board game has vignettes which are developed based on real life situations and experiences of older adults living with ageing related challenges. The game is played in phases where the player first sets-up a house and neighbourhood for the character based on their living and financial situations. In further phases, players are then presented with ‘life or health’ related changes to the characters’ lives that need accommodations to their living environment, situation or location.

To support the process of making the character’s home more suitable for their new and changing needs, ‘Adaptations cards’ such as ‘changing bath to shower’, ‘better tap and shower controls’ are introduced in the ‘Adaptation shop’. Each adaptation is tagged with a cost and rating for the cognitive and physical support it provides. The game takes the player through the journey of exploring and sharing their thought and decision-making processes as they work their way through adaptation cards – exposing them to complex factors in play such as limitations to funding, support and options available to create a suitable environment for the changing needs of the character.

When older adults in England played the game (defined as aged 55 and above for the project), their decisions were largely based on lived experiences – as opposed to tenure, funding, permissions. They reflected on their own future plans for ageing at home, drawing from past experiences of caring for an older parent, family member or a close friend. The features of the game (with many adaptation options, a wellbeing rating scale for each phase) allowed participants to choose compassionate solutions for both the older adults and their carers at home. Simple and temporary additional modification solutions like decluttering, adding a chair to the kitchen for resting whilst cooking were considered impactful. The need for future-proofing homes and adopting an intergenerational living arrangement to improve ageing experiences came across strongly.

Key takeaways from the playtests were that people, their needs, and experiences are varied and diverse, which reinforces the need for an individual-focused approach to home adaptations. It is particularly essential for older adults to have control over the decisions and intervention processes, and that their sense of autonomy and self is maintained. This can be facilitated through small and often impactful changes, and provision of more information and advice.

Going forwards, as my research background is in residential psychology and architecture, I am interested in understanding how we can empower older adults to feel more autonomous and capable in navigating this complex home adaptation process. My previous (doctoral) research looked at importance of flexibility in homes for residents’ wellbeing. This includes both having in-built building design features at home (futureproofing) as well as empowering residents to engage in the behaviour of modifying their homes such as adaptations and personalisation. My thinking around the need for looking at both housing designs and resident behaviours simultaneously for better residential wellbeing is outlined in my previous HSA blog. On my current year as an ESRC Postdoctoral Fellow, I am examining how capabilities and behaviours associated with home adaptations and modifications can be facilitated through home designs and what the practice and policy limitations are, with residents, housing designers and stakeholders.

About the author

Sadhana Jagannath is an ESRC Postdoctoral Fellow at Imperial College London. Her background is in environmental psychology and architecture, with a research focus on integrating built-environment designs with the psychology of its users. Her research focus is on user behaviour, control and empowerment within housing and healthcare environments through design, with implications for long-term sustainability of human and planetary health. Her research vision is to conduct applied and impactful research in this area to advance the development/management of built environment designs with human health and wellbeing at its heart.

Sadhana received a bursary to attend the Housing Studies Association Annual Conference 2024. As part of the bursary, recipients are expected to contribute to the HSA blog, and this blog post is based on the paper presented at the HSA conference.